Vito Minoia in dialogue with Shahid Nadeem

- Vito Minoia

- 23 apr 2020

- Tempo di lettura: 7 min

Vito Minoia in dialogue with Shahid Nadeem*

for the European Journal “Theatres of Diversities” in collaboration with International Theatre Institute (ITI-Unesco).

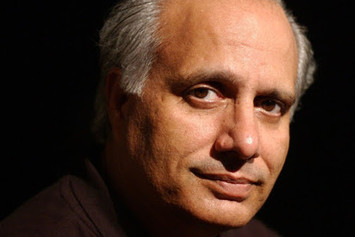

Shahid Nadeem

*World Theatre Day 2020 Message Author (PDF / Video). Shahid Nadeem is Pakistan’s leading playwright and head of the renowned Ajoka Theatre.

Since early childhood, yours has been a life of migrations due to war and political upheaval. How much did this affect your education?

I think the experiences of migration have enabled me to stay away from rigid and xenophobic patriotism. I have developed associations with people, not he political or religious identities. One other trait I have developed, as a self-defense mechanism perhaps, is to move on and not to look back.

However my education did not suffer that much .

During your studies in Psychology at the University of Punjab, you wrote your first play. Can you tell us about your first experience and the enthusiasm that drove you as a university student and inspired your desire to change the world?

Late 1960’s and early-70’s, when I was a student, were times of major political and social changes in Pakistan (and the world over).The youth was becoming more radical and assertive. I was full of revolutionary enthusiasm and optimism. I believed the socio-economic system was unjust and corrupt and wanted to play a role in bringing about a system which was just, egalitarian and modern. I started with activism in students politics and leading a students revolt against the military ruler Ayub Khan. I was imprisoned and thrown out of the university for my “political” and “subversive” activities. But I soon realized that the real change required a change of mindset and change of worldview, “a change of heart”. I had been writing short stories as a hobby. Then one day my university received an invitation to participate in a theatre festival at the premiere girls’ college, Kinnaird. A friend, interested in theatre, asked if I could convert one my stories into a play. I agreed. A young man would do anything to see the Kinnaird from inside. The play was a great success and that was the beginning of my career as a playwright. I realosed I could do a better change bring about a “change of hearts” and leave the change of system to others. By the way, I learnt much later that, among the audience at the Kinnairds, was a girl who was profoundly impressed by the play. She was Madeeha.

Can you tell us about your exile in London and your growth as a playwright for the Pakistani dissident group Ajoka, created by Madeeha Gauhar, who later became your wife?

I wrote a couple of plays and then stopped as there were no theatre groups to produce my plays. That was the time of yet another Martial Law in Pakistan. I was arrested for opposing the military rule and imprisoned before being exiled. It was during my exile in London, where I met Madeeha who had just set up Ajoka Theatre. That was the beginning of our playwright-director relationship which ended with tying the knot and eventually my return to Pakistan.

Madeeha, who passed away on April 25, 2018, was an actress, director, and human rights activist and fought through theatre for social change and peace between Pakistan and India. Can you tell us about the quality of her work, which was focused mostly on women's literacy, the defence of the rights of girls and against honour killings, and in support of health and family planning?

Madeeha was a remarkable person, full of energy and a rebellious spirit. From her days as a school student, she got interested in theatre and this zeal became stronger and stronger, to the extent of an obsession. It was because of this all-consuming passion that she was able to found a dissident theatre group challenging the draconian military rule of General Zia ul Haq. Inspired by her socialist mother, Khadija, Madeeha broke the taboos and addressed themes such as honour killing, religious persecution and war-mongering. Her unrelenting support in developing relations with Indian theatre groups and peace campaigners won her admiration on both sides of the border. Her death was mourned equally by theatre and peace group in India and Pakistan. Her contribution as a director is unsurpassed in Pakistan. She was committed to ideals of Peace, secularism and gender equality but as director she was equally interested in the cultural exploration, theatrically embellishment and linking up with traditional theatre forms. Once she got a script from me, she would spend a log time exploring the possibilities of musical score, costumes, set design and a very tough rehearsal schedule.

"Barri", one of your most performed works, directed by Madeeha Gauhar, highlights the suffering of four women detained in a prison cell: an activist, a mother arrested in place of her son, a dervish woman accused of dancing in a sanctuary, and a young woman who killed her elderly husband three times her age. What is the link between them and which part of wounded humanity is highlighted?

A system which condone or promotes violence against women, can not be a just system. It inevitably condone and promotes religious discrimination, class oppression and human rights. In Pakistan, women have been in the vanguard of the struggle for human rights and human dignity. “Barri”, at one level narrates the stories of four women from different social backgrounds and incarcerated on different charges but it also provides insight into a society where the ruling political and religious elite is creating havoc with the downtrodden and vulnerable. It is a damnation of a patriarchal, feudal, class system and also a critique of the elitist nature of a faction of the feminist movement in Pakistan.

You have been incarcerated three times under various military governments for your opposition to the regime and have been adopted as a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International. Antonio Gramsci, an imprisoned intellectual who died in prison in Italy during fascism, to whom our magazine dedicated the International Theatre in Prison Award in 2016 under the patronage of the International Theatre Institute (ITI-Unesco), said that prison is an institution that produces "molecular" changes in the person. How much did theatre help you survive imprisonment? We read that in the infamous Mianwali prison, you started writing plays that were later put on by and for the prisoners. Would you like to tell us a little bit about that experience?

Prison experience indeed brings about the best (or the worst) in you. You are on your own, at the mercy of a dictatorial, and often savage, prison regime. During the day, you are preoccupied with the hard prison labour and finishing your daily quota. But when you are locked up in a cell or a prison barrack, the loneliness hits you like a log. Some cry, some fight with others, some pray, some play cards. Some write letters or wait for the weekly visiting days. I noticed that inevitably some one would start singing a sad song and others will gather around him. Then imperceptibly lighthearted group singing would start, lightening up the somber mood in a dark cell or barrack. Then someone would start telling an interesting personal or folk tale. I realized that some kind of entertainment, story-telling was a desperate need for all of us. That's when I got this idea of linking and developing the anecdotal theatrical elements which were already there. The response was unbelievable. I discovered that there were hidden writers, actors, dancers, make up artists, costume designers and actors in my prison-mates. And mind you they were not political prisoners, they included murder convicts, smugglers, spies, thieves. But their crimes did not prevent them from being humans, willing to entertain or be entertained. We would rehearse all week and perform over the weekend. The appreciative audience included prison guards who would watch from outside through the bars. If we missed a performance, they would be equally disappointed.

How much can this experience help us today in a planet struggling with coronavirus and forced social isolation?

Prison are forced isolation from our families and friends. Like our prison plays, people who have been forced into isolation, can and should find ways to entertain themselves, give themselves a relief from the frustration of isolation. Unless advised to self-isolate, they can have family plays, puppet performances or music sessions. The social media and smart phones have opened limitless possibilities for online performances. We at Ajoka had an online meeting on the World Theatre Day and have decided to convert our theatre activities into online theatre. Isolation is a physical phenomenon but no one is stopping us from keeping the spiritual and social bonding.

Ajoka's mission, which you direct in Lahore in Punjab, is to work for a democratic and egalitarian society through art-based initiatives. What results have been achieved in recent years, and how do you face new social and cultural challenges?

As a theatre group, we have certain limitations, physical, financial, technical. But we are irreplaceable as a provider of direct, dynamic and live interaction with our audience. Our audience come to the theatre venue, to share the theatrical experience with theatre-makers and also with other members of the audience. No doubt the Corona crists has put a stop to such inspiring collective sharing but I am sure this crisis will also be over, sooner than later. In the meanwhile let us explore other forms of theatrical interaction. Such challenges may lead to the development new forms of theatre.

In many of your plays, you address the issue of religious opposition in South Asia. "Theatre can uplift the stage, the performance space, into something sacred," were your words part of a beautiful message you wrote for the international community for the 58th World Theatre Day. How important do you think spirituality through theatre is and how can this be manifested?

We in Pakistan and in the region have recently seen grave challenges of religious extremism and violence. Narrow-minded interpretation of religion have pitted one faith or sect against the other. On the other hand, spiritual and cultural traditions have presented a powerful and popular alternative which can heal the wounds of extremism and bring humanity together. We can reach out to the sections of society which is not familiar with theatre, or not well-educated and entertain and inspire them. We can link up with the folk theatre which is part of the people’s heritage. Theatre can touch the hearts through powerful performances but through a spiritually-rooted theatre, they can touch even the souls of their audience.

Vito Minoia, Professor at the University of Urbino (Italy), where he founded on 1990 the Aenigma University Theatre. Director of European Journal “Catarsi-Teatri delle diversità” (Catharsis-Teatres of Diversities), President of Internation University Theatre Association, Coordinator of International Network Theatre in Prison.

Commenti